The Center for Brain/Mind Medicine > Support & Education

For Family & Friends: Supporting the Primary Caregiver

If you’re reading this, chances are you have a family member or friend who is a primary caregiver for a person with Alzheimer’s Disease or a Related Dementia (ADRD). We welcome you to the dementia community. We’re here to connect through sharing our experiences, offering support, and continuing to increase our understanding of how to live with and support those with ADRD. As a family member or friend, you can enhance the richness of day-to-day life of a person with ADRD and their primary caregiver in various ways. Below you will find a brief introduction to dementia and the unique role of the dementia caregiver. There are also suggestions for how you can help.

What Is Dementia?

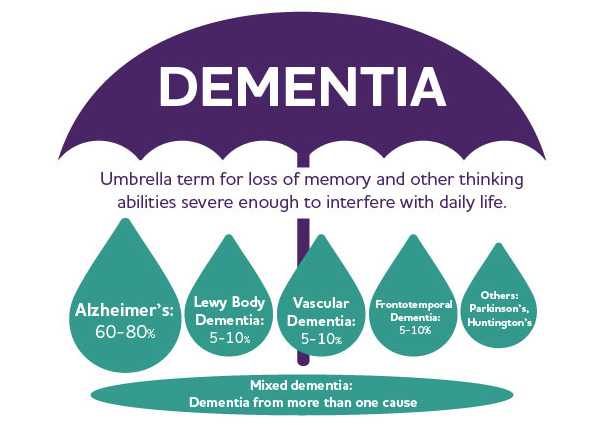

The term dementia refers to any condition that causes a gradual decline in cognitive abilities and behaviors, ultimately interfering with a person’s functioning on a day-to-day basis. Dementia is an umbrella term, not the name of a single disease. Sometimes it’s called a neurocognitive disorder. With aging, we expect changes in thinking and behavior, but dementia describes a process that is much different from normal aging. To learn more about how normal aging differs from dementia, click here.

Types of dementia include Alzheimer’s Disease, Frontotemporal Dementia, Vascular Dementia, and Lewy Body Dementia. Alzheimer’s remains the most commonly diagnosed, with one in nine people (11.3%) age 65 and older affected (Alzheimer’s Association 2021 Facts & Figures). Two-thirds of those diagnosed with Alzheimer’s are women. African-Americans and Hispanics are more likely than white Americans to have Alzheimer’s and other dementias, although they are less likely to be medically diagnosed. To learn why, read more here.

Image credit: Alzheimer’s Association

Although the underlying cause of dementia may vary, all dementias damage the brain’s circuitry. Symptoms vary depending on how much and where the brain is impacted. Changes may be seen in these areas:

- Attention and concentration (how long they can stay engaged with a task)

- Executive functioning (how they plan, reason, and make decisions)

- Memory (how they learn and what they remember)

- Language (how they speak and what they understand)

- Perception (what they see, hear, and feel)

- Motor functioning (how they walk, write, etc.)

- Understanding social norms (whom they feel comfortable interacting with and what they talk about)

Since dementia processes are progressive, these changes require more and more involvement from others to support daily living. If you want to learn more about dementia, click here.

How Is Dementia Caregiving Different From Other Caregiving Roles?

Dementia caregivers assume various physical and cognitive responsibilities, but they also face the loss of the person themselves over time as a result of the dementia process. The dementia caregiving role is unique in its many uncertainties: the timeframe of the condition, how the process will unfold, and what changes may surface on a daily basis. No one can give dementia caregivers answers to these questions. Dementia caregivers also wonder whether they are capable of caring for their person over time. Caregivers come to realize that change is the only constant.

Family caregivers of people with dementia, often called the “invisible second patients,” are essential to the quality of life and wellness of people with dementia. Multiple studies show that dementia caregivers experience:

- Increased risk of high blood pressure, elevated levels of stress hormones, impaired immune function, slow wound healing, and coronary heart disease

- Higher rates of depression, anxiety, and social isolation compared to others their age

- More caregiver burnout than those caring for people with other chronic or terminal illnesses

Dementia caregivers provide:

- A longer duration of caregiving than those caring for people with other conditions

- Billions of dollars of unpaid care each year

The more burden a dementia caregiver experiences, the more difficulty they have managing challenging dementia behaviors (aggression, self-harm, wandering, etc.).

An Ongoing Process

Caring for someone with ADRD is a marathon, not a sprint. After a fire, death, hurricane, or birth of a child, meals are provided, phone calls and text check-ins happen, and people make themselves available immediately. This surge of support, when people “rise to the occasion,” is like a sprint. Caring for someone with ADRD is a marathon, one where the mileage, terrain, and weather are unknown. The primary caregiver is in it for the long-haul—planning, problem solving, and strategizing at every stage. Just when a caregiver feels like they have set a pace, the terrain or weather changes unexpectedly. Runners get cramps—physically or emotionally—and this is how it can feel on a day-to-day basis for dementia caregivers. Dementia caregivers often feel alone and isolated as a result of the length of the caring needs and role.

This Sounds Awfully Hard. How Can I Help?

Marathons are hard, and marathoners don’t do them alone. They need running buddies, people handing them water along the route, and friends who show up to cheer them on. Other volunteers work behind the scenes to make the marathon go smoothly. Fortunately, there are many ways you can support your friend or family member who is a primary caregiver, and the person with dementia, too. Many studies have shown that support from family and friends reduces caregiver stress. Offering your time, energy, and continued companionship is of great value to everyone in this marathon. Here are a few tips and suggestions from dementia caregivers about what is helpful—and what is not.

Tips

- A great first step: Ask the person with dementia and/or their primary caregiver how you can be of help. Be prepared to ask throughout the journey—their needs will change.

- Continue to educate yourself: To adjust to the changes you see, there may be times when you need more information to know how you can be of most help. Look through the online resources in this website, or read one of these books.

- Get involved from the beginning if you can: Stable, ongoing relationships are best for the person with dementia, their primary caregiver, and you.

- Depending on the situation, a specific offer of support may be greatly appreciated—for example, “This week, I can drop off dinner on the weekend or take your person for a walk Thursday morning from 9-10am.”

- Be consistent with your help: For example, come by every other Tuesday afternoon for a visit or pick up groceries once a month.

Feedback From Caregivers

The gift of time:

- Take the person with dementia for an outing for several hours to give the primary caregiver time alone.

- Spend time with the person with dementia while the caregiver runs errands.

- Coordinate a weekend away for the caregiver.

- Offer to complete tasks such as calling the cable company to fix a problem.

The gift of energy:

- Offer to run an errand, clean the house, make freezer meals, etc.

- Drop off a care package with a note of support.

The gift of your friendship:

- Caregivers fear they will lose important relationships as a result of cognitive and behavioral changes in the person with dementia. Connect regularly. Stay in touch. Even sending a text can help.

- Offering a judgment-free space to share challenges, frustrations, and fears can go a long way to helping the caregiver decompress.

- Accompany your friend/family member to a dementia caregiver support group or educational event. Call in advance to make sure friends/family members are welcome.

Click here for a printable list of ways to support dementia caregivers.

Things to Say

- “How are things going?” “How is [person with dementia’s name] doing?” Sometimes people think asking will be stressful for the caregiver, but the opposite is true.

- “I hate that you’re going through this.” A simple acknowledgement of difficult circumstances can be comforting.

- “I don’t really know what to say right now, but I’m here if you need me.” We may not always know the right thing to say. Sometimes your presence during hard times is the most valuable offering.

- “You’re doing a great job.” Words of encouragement can boost confidence and lift spirits.

- “I’ve been thinking about you. Would you have time for a visit this week or next?” Caregiving can be lonely, and getting out can be challenging. Remind the primary caregiver that you’re still a friend. Try to be flexible about when and where you can meet.

- “I’m on my way to the store. What do you need?” Having help offered instead of having to ask can be a stress reliever and a reminder to primary caregivers that they are not alone.

Things Not to Say

- “They seem fine to me“ or “Oh, I do that, too.” Often intended to offer reassurance, these comments can minimize the caregiver’s experience.

- “You should…” Avoid giving unsolicited advice. Think about whether this is a time for problem solving or just providing a safe space for your friend/family member to be heard.

- “That’s too much for you.” Usually motivated by a desire to protect the primary caregiver, this statement can instead undermine their autonomy.