David Weinberg

David Weinberg is a former BWH pathologist who developed a second career in photography. He became a caregiver when his wife, Louise, developed atypical Parkinson’s disease and experienced significant physical and cognitive decline in the last few years of her life. He documented her experiences with Parkinson’s disease and Parkinson’s dementia is a series of photographs in collaboration with Louise. Through her descriptions of her hallucinations, he constructed images that she agreed closely resembled her visual experiences. Her hallucinations typically consisted of passive figures who did not speak or interact with her, faces draped in cloth or stockings, small animals, and children. Although she found these images bothersome, they were generally not frightening. In fact, she found some hallucinations mildly entertaining.

In 2019, they exhibited her artwork and his photographs in a joint show at Galatea Fine Art in Boston, entitled “If You Could See What I See.” Louise died in 2021, and continued to find enjoyment in making art until the very end.

Joe Wallace

Joe Wallace was first trained as a journalist. He has been a portrait photographer and storyteller for twenty years. Like many, Joe has a deeply personal connection with dementia. His maternal grandfather and hero, Joe Jenkins, had Alzheimer’s. His maternal grandmother Elizabeth Ponder (Bebe) had vascular dementia. And in recent years, his mother Barbara has begun her journey with the disease.

Joe was frustrated by the common, one-dimensional narrative of dementia—futility, despair, and loss. These are real and important elements of the dementia journey, but by focusing only on the narrowest of views, do very little to change the stigma of those living with the disease. In many ways, showing the stereotypical perspectives only makes it easier to continue ignoring the burgeoning health crisis and the individuals themselves.

Joe feels strongly that to give the audience courage to act in ways large and small, you must to show the whole story. The artist must not be afraid to show not only the fear, loss and despair, but also the love, connection, dignity, and powerful humanity that always remain—in the subjects, in the care-partners, and in the families and communities. That is the only path to evolve the narrative and have a positive social change.

See more Portraits of Dementia

Charles Contant

I took these images on a once-in-a-lifetime trip to Australia in 2018 to see my daughter receive her PhD. It was a couple of months past the two-year anniversary of my craniotomy for a meningioma. That surgery affected my right frontal lobe, and greatly diminished my ability to do algebra and write computer code. Not a good situation for a professional statistician. However, I honestly believe it opened up my appreciation for visual beauty. Colors, shadows, patterns all seem to become deeper and have more flavor. They also captured some of the emotions I felt, both at the time I was looking, and of my general emotional state. I still take images of objects that mean things to me; birds, people and, especially, color and shadow.

Two Lily Flowers on the island of Tahiti

Actually, there are two flowers and a bud. The vibrant color of the flowers, against the dark background of their pond, was an obvious picture I wanted to save. They are full of the light and vibrancy of their life. Yet, underneath the flowers and lily pads is the dark water in which they thrive. I find this image hopeful.

Beach in Australia

I love the contrast and shadows on this beach. It was later in the day, and the sun had just broken through the overcast sky. The shapes of the little sand mounds, the long shadows, the tufts of grass holding on to the beach, even the gray sky, all seemed to make a wonderful set of visual textures. It might look like a sad scene, but I thought it was a powerful play of light and color. Reminded me how things can change with the light and wind and time, and create beauty.

Puppy on the Beach

This image is not from the Australia trip; it is from a trip we took to Aruba about 8 months before the Australia trip. We had gone to Eagle Beach, which is beautiful in itself. I was lucky to catch this guy running along the beach in the sheer joy only a puppy can have at being alive. He jumped up to catch something only he could see, and here he is in midair, with the setting sun behind him. Life has joy.

Olivia Parker

From Olivia’s website: After graduating from Wellesley College with a degree in Art History, Olivia Parker began to make and photograph ephemeral constructions in 1973. Represented in major private, corporate and museum collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Hirshhorn Museum, The Peabody Essex Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Parker’s work has been published in four monographs and in numerous magazines in the United States and internationally. She has had over 100 solo exhibitions in museums and galleries in the United States and abroad. Also, she has lectured extensively and conducted many workshops. In 1996 she received a Wellesley College Alumnae Achievement Award. Residencies include Dartmouth College, The Aegean Center for The Fine Arts, MacDowell Colony, Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, and Cassilhaus. In 2022, Lesley University awarded Parker with an Honorary Doctorate of Fine Arts.

A skiing accident in 1995 ended Parker’s view camera photographs. Unable to work in the studio or darkroom for a year because of a shattered leg, she experimented with computers and digital software. As software and equipment improved, fine images and stable prints evolved. Although Parker misses making silver prints, new ways of photographing with digital cameras have opened worlds. “Digital allows me total freedom to experiment without worrying about film usage or precise camera set up. In the beginning, view camera work was, however, a much better teacher for me than digital would have been. It made me slow down, consider image edges and think about the dynamics of what falls between the edges.”

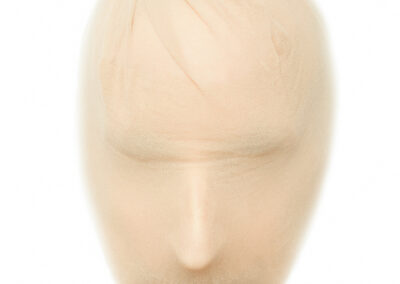

In 1987 Parker said in the introduction to a book of her photographs, “I am interested in the way people think about the unknown… New ideas form, the old are shattered, and sometimes old ideas pop up again among the new like graffiti on a wall. All is uncertainty and change, but optimists and bingo players are on the lookout for moments of perfect knowledge and perfect cards.” At present, Parker is working on a series of photographs on Alzheimer’s called, “Vanishing in Plain Sight.” These images are Parker’s speculations as to what happened in her husband’s mind as he was overcome by the disease.

View more photographs from this series

Torrance York

Semaphore examines the shift in my perspective after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease nine years ago. Through images, I consider what it means to integrate this life-altering information into my sense of self. What does acceptance look like?

Post-diagnosis, everyday items and encounters take on new meaning. Simple tools now present a challenge, and uncertainty pervades the periphery. As I look around me, the branches of trees become networks of neurons. Using photography to capture my fears, challenges, and aspirations has facilitated my understanding of the disease and strengthened my hope for the future. Optimism holds the key for me right now. Light, always an inspiration, illuminates a path for me to follow. In pursuit of this path, I created Semaphore.

In their 2023 book Your Brain on Art: How Art Transforms Us, authors Susan Magsamen and Ivy Ross define the evolving field of neuroaethetics (or neuroarts) as “the transdisciplinary study of how the arts and aesthetic experiences measurably change the body, brain and behavior and how this knowledge is translated into specific practices that advance health and wellbeing.” Neuroaethetics helps explain the benefits I have garnered from making Semaphore.

Parkinson’s disease is the world’s fastest-growing brain disorder. Currently, over ten million people live with Parkinson’s worldwide. My initial ambition for Semaphore, to foster a greater understanding of living with Parkinson’s and encourage dialogue that includes the often-taboo subjects of illness and vulnerability, has expanded. From this new perspective, I advocate for the arts as a force to benefit the health of our bodies, brains, and spirits. While Semaphore is relevant to the Parkinson’s community, it also connects with others whose journeys require growth, patience, and perseverance to move forward.

For more information about neuroaesthetics visit www.yourbrainonart.com.

Torrance York earned a BA from Yale and an MFA in photography from RISD. In 2022, she published her monograph Semaphore about the shift in her perspective after being diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. Featured in various publications and podcasts, Semaphore has been awarded in Lenscratch’s 2021 Art & Science Awards, as a Critical Mass 2021 Finalist and a favorite book of 2022 by online photography magazine What Will You Remember? Semaphore has been exhibited at the Danforth Art Museum at Framingham State University in MA, and at Rick Wester Fine Art in Chelsea, NYC, who represents her work. Currently the project is on view at the Lightburn Gallery, New Canaan Library, CT through September 7, 2024.

Public and private collections owning York’s photographs include the Addison Gallery of American Art, Andover, MA; Fine Art Collection at Montefiore Einstein, NY; AllianceBernstein, New York, NY; John & Sue Wieland Collection at the Warehouse, Atlanta, GA; and Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), Providence, RI. York has exhibited nationally and internationally at venues such as Fotonostrum, Barcelona, Spain; Littlejohn Contemporary, New York, NY; Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, MA; Schelfhaudt Gallery, University of Bridgeport, CT; Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, CT; and Center for Photography at Woodstock, NY. York was a resident artist at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center and received a Connecticut artist fellowship grant in 2010.

Since publishing Semaphore with Kehrer Verlag (October 2022), York has presented at the World Parkinson’s Congress in Barcelona, to Parkinson’s support groups in person and virtually, and to the Neurology Department’s Grand Rounds at the University of Virginia Medical School to share her experience as an artist and person with Parkinson’s.

Click here to learn more

@torrance_york